This morning, I floss my teeth with vigour as I look out at the volcano, wreathed in a misty smog. If there were a prize for being middle-class, and if this daily ritual of flossing, each tooth surrounded, cossetted individually with purifying dental tape, could ward off sickness, I would win.

A sign at my dentist always makes me laugh. “You don’t have to floss all your teeth. Just the ones you want to keep.” Yet for all my knowledge, and my flossing and my striving, I still got sick, with an illness that spread slowly through my veins and my body until it reached my brain.

I am hoping that scrupulous hygiene this week can ward off any bugs during neutropenia, perhaps one of the riskiest parts of this whole process – when your neutrophils, the white blood cells that fight off attacks, are so low that your body is at its most open to infection from things that your body would normally laugh off.

A doctor who saw me before I left London (not my own sympathetic but part-time GP) was unconvinced when I tried to explain why I was going to Mexico for HSCT, and what I hoped to achieve.

“Stop catastrophizing,” she says, when I explain that I want to stop this disease in its tracks before it is too late.

Then: “You won’t end up in a wheelchair,” she tells me with blithe medical confidence, around one minute in.

But how does she know? I don’t.

And I do know that I am already walking with a stick, because otherwise I fall over in the street. And this doctor knows nothing of me, or the 49 years that make up my life, after a quick scan of the patchy notes on a screen.

The figures suggest that after 25 years of MS, my odds of continuing mobility without a stem cell transplant are not so good. So I can tell within the first few minutes of our allotted ten that this GP and I will not be lifelong friends.

“And isn’t this HSCT treatment a little extreme? It could kill you,” she continued blithely, in ignorance of any actual figures or clue as to what a stem cell transplant for MS entails.

“Now, I must ask you,” as she cocks her head winningly to one side – “what exactly are you doing for your own health?”

I sit silently and look at her, visions of mini Bikini Atoll nuclear explosions in this quiet surgery room playing through my head in black and white. What I really wanted to scream was this:

“I am going to Mexico for a stem cell transplant. Spending tens of thousands of pounds that I don’t have in the bank. Volunteering to have chemo, and be sick as a dog. Worrying my family and friends by going abroad. Having my blood and immune system changed radically and for life in a foreign country by doctors and nurses whose language I don’t speak or understand, muchas gracias, because our health system here won’t offer this to me, despite my years of paying taxes and national insurance since my early twenties, although God knows, I’ve tried.”

But I didn’t. Instead, I said in a tone that tried to dampen down any bitter sarcasm, that I had been drinking green tea, eating my five fruit and vegetables a day and attending yoga classes for the past ten years, as was my birthright as part of the British urban female middle class.

And given up alcohol altogether, and smoking. I was, and had been for several years now, officially a fun-free zone. And I still had MS, which no amount of flossing, vegetables, yoga or green tea had managed to budge, although perhaps they did help fend off greater disability awhile.

The doctor’s eyes lit up. Tick! That’s what it says on the NHS box: advice on lifestyle communicated, written promptly onto the waiting computer screen. The doctor nodded with satisfaction, said she would discuss my case with colleagues, and called for the next patient.

Today, I am a patient now quarantined at the apartment at Inspiralta since my stem cells were returned to me. And after the flossing this morning came the wrapping.

Joy, my nurse, has been gently nagging me about the shower. The one I didn’t want to have while the alien was inside my chest. I promise that I did have a flannel wipe each day that it was in (I am not beyond hope yet) but the thought of dislodging or angering the sleeping serpent PICC line with a shock of water was too grim.

So today, to protect the bandage that’s now in place to shield the tiny scar that remains on my chest, Joy found a plastic bag, which she cut up, and began to plaster gently over the white gauze square. Slowly, and with fierce concentration, she tenderly wrapped up my shoulder and taped on the clear plastic, and finally looked at her work and saw that it was good, knowing she’d wrapped me up as efficiently as any parcel to post me on towards the land of the clean.

As I shower, enjoying the velvety plish of the water on my skin, I hope that beneath, inside my veins, the tiny stem cells now exploring their way through their new home are finding everything to their satisfaction as they start to move in. These young ones are making me tired today. I feel a little like an elderly new mother, exhausted after the joy and the rapid seesaw of emotions of giving birth. I am keenest of all on the idea of sleep and rest, as the raw physical toll of the past few days has made itself felt on the body and the mind.

But I can’t help but laugh as I wash, being careful not to get my shoulder too wet. Joy’s eager wrapping had put me in mind of the joyful Berlin summer of 1995, the year that that the plans by the artist Christo and his now late wife Jeanne-Claude finally came to fruition, and they completed their meticulous wrapping of the Reichstag, the German Parliament building, in the reunited German capital.

At first, like many Berliners, I was sceptical and slightly querulous. Moving back to Berlin in 1993, I had taken on the very nature of my adopted city with pride, in my first post abroad as a BBC reporter. The corporation’s German business reporter, no less, which would have come as something of a surprise to my family’s old friend, the wonderfully-named German banker Kurt Kasch.

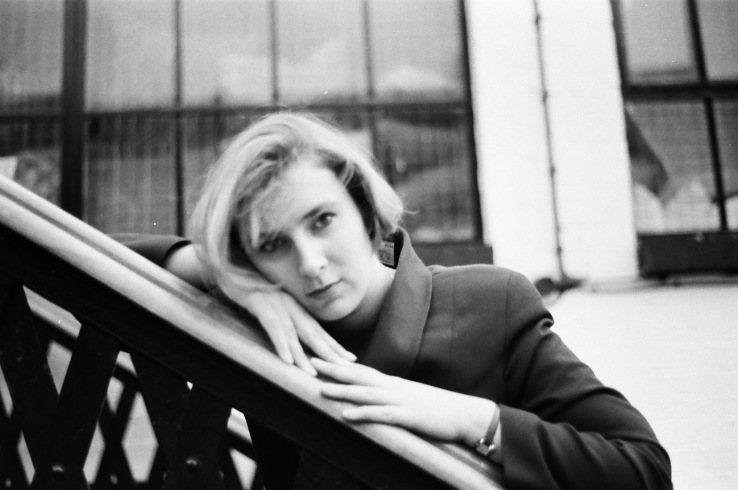

He had employed me as an intern at the Deutsche Bank during an earlier life in Berlin, back in 1984, when my father was based there as a diplomat and a widower, and I was a teenager fresh out of boarding school.

I had just finished my A levels, and was eager – in theory – to learn proper German and the dark arts of banking and finance. Or at least my Dad was very keen for me to do so. Where better than here in West Berlin, just down the road from where we lived in splendour in Ulmenallee, in the 1890s architectural solidity of the Prussian bourgeoisie.

But at 17, I was not so eager to start work at 7am. Nor able to arrive at work, it seemed, without a crashing hangover after yet another interesting evening in a darkened bar or club in one of the edgier areas downtown. Officially, I was at my best friend in Berlin Cathy Wigmore’s house. And officially, she was at mine.

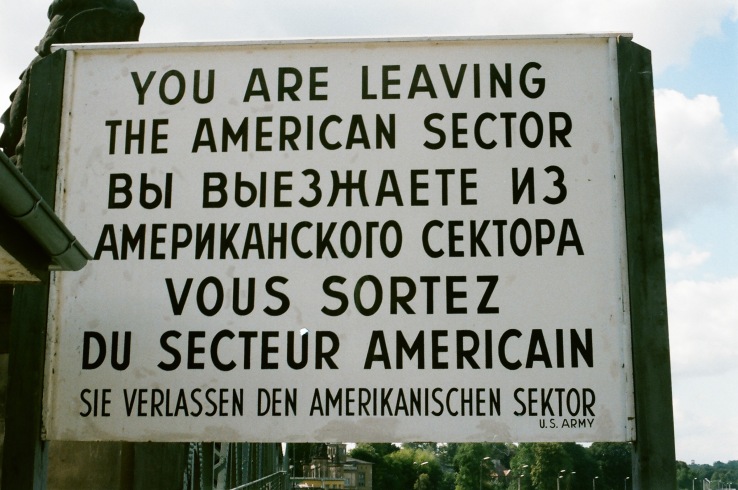

It didn’t help my nascent career in banking. For every afternoon at 4pm at my bank branch in the British Sector of Berlin, on Theodor-Heuss-Platz, after I’d served and changed pounds into deutschmarks for another British soldier or his family, the cry would go up: “Storno!”

Annul or cancel that transaction. “Frau Wyatt, please come here…”

In those pre-computer times, I always got the exchange rate the wrong way around, usually in the customer’s favour. Even kindly Herr Jelinek, the paternal white-haired cashier, was getting rather tired of this, and could only cover up for me for so long.

So the bank found the ideal bureaucratic solution. They sent me to head office, on Otto-Suhr-Allee, gave me a typewriter and a telephone, and absolutely nothing to do.

Or at least nothing that I can remember now. Sitting in the peaceful little annexe outside Kurt Kasch’s office, I wrote reams of bad poetry, limericks and short stories, and an annotated list numbering the appeal and the downsides of every boy I knew. The list was growing satisfactorily, after my seven long years at an all girls convent boarding school. Ten names in all by then, rated by (apparent) intelligence, looks, ability to flirt and at the end – with a hopeful query – has car?

I found the list while clearing out my flat the other week. I think I’d kept it to be shared and giggled over with the mischievous Cathy when we were all grown up, and she the responsible working mother of three young children in our later years. I hope I did show it to her one last time before she died too young of cancer in June 2015. She never did reach 50. But even in death, she still lights up my memory as the girl with the greatest spark of life I have ever known.

On some days that winter at the Deutsche Bank, I even tried in a desultory fashion to master German grammar, judging from my notebooks from the time. But it continued to evade me, just as Manfred von Richthofen, the Red Baron in his Fokker tri-plane in the First World War, long outwitted even the skills of the most dogged pilots of the nascent RAF.

The RAF was still based in the Berlin of the 1980s, part of the four power agreement, mostly at RAF Gatow, while Cathy’s dashing father Wing Commander Bruce did something terribly important to do with Air.

Everyone we knew in the Berlin of those blissful Cold War days did something awfully important to stop the Soviets invading. Including my and Cathy’s dad. Even the young subalterns at Spandau barracks and elsewhere did their bit, standing ready every day to defend, albeit on some days it was a slightly more hungover slouch.

From the 14th/20th Kings Royal Hussars to the Queen’s Own Hussars exercising and endlessly servicing their tanks, or the junior officers of the Devon and Dorsets cleaning and shining their Sam Browne belts and their weapons, all appeared ready and eager to fight if the Reds did try something funny over the Berlin Wall. As long as the young men weren’t at that point singing their lusty lungs out in the Irish Harp downtown, always a popular venue with the Brits.

The subalterns’ merits as defenders of our freedom, and potential attackers of our virtue (aka possible boyfriends), were our main concerns that year. They were debated often and eagerly by Cathy and myself, both former convent girls, sometimes with advice from her older brother Andy, then a worldly 18-year-old sorting LPs at the British Forces Broadcasting Service library. My father always said he’d end up either very rich or in prison, or maybe even both.

Back at the bank, I may have tried to translate some German bank documents once or twice at the behest of my new boss, but soon even that dribble of documents dried up. I had gone too far.

Inevitably one day, Kurt Kasch called me in to his office and looked me straight in the eye. “Frau Wyatt, it is clear that banking is not for you,” he said. “I’m afraid we cannot keep you here at the Deutsche Bank.”

For me, the bank was over. My cheeks burned red with shame. I’d let my father down, as well as my then new, soon to be stepmother, Wendy, now affectionately known as WSM, short for Wicked Step-Mother, whom I’d been so determined to impress.

And yet, inside my heart like a furnace, a rebellious pilot flame of joy lit up and exploded with glee. Finally, I was free! Free at last after three or four months ruled by the ghastly tick tock of the clock, doing something I was no good at, in an office as silent and final as the grave, when ahead of me could lie a glorious adolescent Berlin summer full of exciting possibility.

I’d secretly been scouting other jobs that I might be able to do, as I had a sneaking suspicion that the end might be nigh for me at the Deutsche Bank. It became obvious the day that I was unexpectedly taken (as a very special treat) to visit the Berlin Stock Exchange to find out how it worked. I still remember it in all its glory, but what sticks in my mind the most are the loos. So hung-over was I that day that I spent much of it there, failing to impress my latest boss.

That spring in Berlin, I’d been much taken with the idea of radio. On the airwaves across all four military sectors of the city, the radio stations competed for friends and listeners and influence across East and West, with Elvis and Levi’s blue jeans far more potent weapons against Communism than any tank. In West Berlin, a friend of mine Stephanie worked as an intern at AFN, the American Forces Network in the Gruenewald near the US PX postal exchange and shops in the American Sector of Berlin.

Stephanie didn’t have to go to work very early, nor ever seem to do that much at all, which appealed to the adolescent me. Best of all, there was an endless supply of exotica in the AFN kitchen, such as the hot-dogs and popcorn ready to be reheated in a magical machine. They called it a microwave oven.

It was thanks to the magic of Wendy, my WSM-to-be, that my father’s explosion of rage was not worse that day when I went home to tell him of my sacking by the Deutsche Bank.

Work in radio instead? RADIO? And a splutter, the click of another cigarette lit, and the exasperated shaking of the paternal head behind a Times newspaper as he sat in his favourite chair.

Radio? That’s not a career, he muttered.

But patiently, slowly, Wendy persuaded him that perhaps it might not be so bad after all. And that perhaps adding up or rather subtracting money at a bank was not really my thing, though clearly many later global bankers had flourished with similar skills to mine.

And reader, a mere week or so later, I did go to AFN as an intern. And they were wonderful. I didn’t do much there, but I helped research and collate the local news and the weather. And do voiceovers for summer specials, and sometimes even a little voiced introduction ahead of the DJ’s spiel. In more advanced months, I was allowed to spin the spools on a videotape editing machine to cut out the ads from a wondrous informative thing called the CNN news feed before it could be rebroadcast on US Forces TV.

All in all, 1985 was a very good year. Out of my greatest humiliation at the bank, I’d found a job I loved. Even if it paid peanuts, and I had to supplement my income by working as the world’s most inefficient gardener for the British Military Government, and later as an employment clerk, sorting endless life-sappingly pointless files noting down every time corporal x took a course, or he and his family moved to housing block y. For me, Cathy, Andy and Stephanie to be young in Berlin in that year was very heaven.

Fast forward on that videotape machine to the Berlin of a decade later, the year I turned 28, and Christo’s wrapping of the Reichstag: a building that had stood for German democracy, in success and deepest failure. Built in 1894, burned in 1933, and almost destroyed in 1945, by Russian forces in the Battle for Berlin, their graffiti (mainly ‘Igor woz ‘ere’ in Cyrillic) later kept visibly on the walls by Norman Foster as he built it afresh for the new reunited German democracy, the building’s power – formidable though it still was – seemed old and spent in 1995.

Nonetheless, that April and May, we filmed and recorded the preparations for the BBC and clambered onto the Reichstag roof, in its then flatter iteration, to watch as burly Berliner work-men threw tough silvery hessian fabric over each and every nook.

Suddenly, one day, like Christmas morning in June, Berliners were invited to admire what had happened in their midst. Instead of a dour, gruff Teutonic slab, a magical silver waterfall of a building stood on that same site: the Wrapped Reichstag. We were indeed rapt, and the city came to celebrate and play for two magical weeks, on the then open land so close to the scars of No Man’s Land left by the snaking trail of the Berlin Wall.

Once again but quite differently, joyously, the Reichstag was fragile, its garb impermanent. A palimpsest of wonder; layer upon layer it gave its new meanings afresh. It was the perfect metaphor for Germany itself as East and West reunited: still in the process of becoming, not quite sure what it yet might be or mean for the Europe and the Germany of our times. We’re still finding out today.

The silvery fabric, shaped by the blue ropes that wrapped this idiosyncratic gift from Christo to the nation, somehow revealed the very essence of the Reichstag beneath, while shrouding it in magic every day, at sunrise and at sunset, each reflected in its playful lustrous wrapping. And we knew in those weeks that we’d never really looked at it properly before, or seen it truly, before Christo revealed it to us anew.

I feel a little like that today about my own wrapped body, though the plastic for the shower has now come off. I have no idea what this body will become, because it’s still in the process of becoming, of being shaped anew.

The stem cell workmen and women of my inner veins are only just beginning. And in the next few weeks and months, they’ll still be fragile, adolescent, unsure of who they are and what they want to do in life.

And even later on, my body will still bear the scars on my brain that MS has caused it through the years. Though perhaps like the ever-changing ground around the Berlin Wall, it may in the decades to come be harder to see those marks or feel the damage done.

It’s sunset now in Puebla. Today I had meant to tell the story of Popocatapetl, and the legend of his life and loves, as sent to me by a friend. But I got distracted, as a toddler does, by all the wrapping. And now it’s getting late, and like Scheherazade in the One Thousand and One Nights, I must sleep. The volcano can wait until another day.

Like the Reichstag of 1995, I have been well-wrapped today, albeit with less spectacular results. I am at least clean, but my glands are swollen, and I’m tired. Soon I may slip into neutropenia and a more somnolent week. So I must go now, for I have to keep flossing my teeth.

This is such a good blog to read, thank you so much. Sleep well.

LikeLike

As a fellow MSer I’m following your blog with great interest, I too was diagnosed later in life (45) and have spent the last 2 years learning how to walk again and adjusting to this new life, a life I don’t particularly like. I too have been told no to stem cell treatment by the NHS, apparently I need to have another relapse, as if the last one wasn’t catastrophic enough. I wish you all the very best as you begin the journey of new life, your resurrection.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for your blog. My husband goes in September to Monterrey for HSCT and I’m finding great encouragement from your words. What a beautiful way of expressing yourself you have and you weave the stories so well. Best wishes for your recovery!

LikeLike

Merde alors, what a hoot of a blog. What a tour de force at this stage in your treatment. Take the best care of you. Love and best wishes from SANTIAGO. I am sending a pic of an exhibit at the superb preColombian museum a further addition to your Crapper experiences. Xxx

LikeLike