I woke up in a field of lavender this morning after sleeping the sleep of the dead. All the way through, from midnight to 8am, just as I should. Bliss and joy.

I open my eyes to Joy herself bearing one of my very last Filgrastim injections, aimed at stimulating my dawdling stem cells to do their stuff and my white blood count to rise. She wields it, as ever, with a professional glint in her eye as well as a warm smile, and injects it with no pain for me whatsoever.

Like any line of work, there are some people who just do things well, and with love, efficiency and precision, and some who don’t. Joy is one of those who does.

And I realise, of course, that the field of lavender is not real, nor part of the field of Elysium in the fragment of dream that still shrouds some part of my mind like the mist around the volcano in the early morning as I awake.

The field of Elysium in which I have been slumbering in my dream appears to be the same one that Russell Crowe stands in, as the (fictional Roman) hero, Maximus Decimus Meridius, in Gladiator, the Ridley Scott film that made me weep deliciously with sorrow and satisfaction in the year 2000, as he is reunited with his beloved murdered family after death.

Did you know, by the way, that the Japanese symbol or kanji for grief is the two symbols meaning ‘sadness’ and ‘resentment’ put together? I learned that from the Guest Cat today, a book that I liked, but a lot less than I expected to.

This Elysium of my dreams is also a place of crystal streams and gentle winds, and it is Joy who sent me there for the night, by putting lavender oil on a tissue under my pillow so that finally I could sleep.

Joy is indeed the daughter of Elysium, or at least she is in the German poet/playwright Friedrich Schiller’s Ode To Joy, although of course he never met my Joy, and he was talking about the Divine (although his Ode is still an absolutely stonking one, even if the EU only wanted Beethoven’s music as inspired by Schiller’s Ode, and not Schiller’s words for its anthem.)

Elysium or the Elysian Fields were first the ancient Greeks’ concept of the afterlife, the paradise that the heroic and the very good would live in after death, to enjoy (another) blessed and happy life. Some argue that the very word Elysium comes from the Greek for to be “deeply stirred” with joy.

The key to Elysium being a successful Paradise is not just, of course, that the saved and the blessed must do no earthly toil or labour, so that their hands stay soft and their nails pristine, but that they can rest and watch as those who are not so fortunate labour away nearby.

Pyschological experiments have shown that when given the choice between receiving a gift of a larger sum of money (say £100) while your neighbour gets say £200 or receiving a smaller sum (say £50) while your neighbour gets £25, the vast majority of people will go for the smaller sum. Beggar my neighbour. I think that random fact came from Richard Layard’s excellent book on Happiness, though I have no memory whatsoever as to whose experiment it was.

And we homo sapiens are happiest when we know we earn more than our colleagues or our neighbours.

A few years ago, it was reported that a salary equivalent then to around £50,000 a year of our finest British pounds was the sum needed for human happiness – worth rather fewer of my fine US dollars since Brexit, but it’s been good for my brother Sam and his firm because they export.

And it was Sam who came with me here to Mexico and went with Joy to do the first supermarket shop for me while I unpacked – thank you Sam, because I have a vague memory that you are not so keen on shopping – so the exchange rate is swings and roundabouts, really. And I kept on finding interesting things in the larder today that Sam bought on that very first day.

Sam, if you are reading this – why a tin of cheese soup? What was it about it that caught your eye? I never even knew that there was such a thing. Though I suppose I might try it before I leave.

Earning more than USD $75,000 a year apparently bestows no greater happiness on the recipient, while earning less leaves some needs unmet. The Nobel Prize-winner Daniel Kahneman’s survey found that happiness rose in line with salary, but only up to that US $75,000 a year limit.

Kahneman, working with Angus Deaton (an economist at Princeton rather than the very similarly-named one who doesn’t present Have I Got News for You any more) wrote that: “Perhaps $75,000 is a threshold beyond which further increases in income no longer improve individuals’ ability to do what matters most to their emotional well-being, such as spending time with people they like, avoiding pain and disease, and enjoying leisure.”

And in a not remotely shocking revelation, it also turns out that the emotional strain of negative experiences, such as divorce or sickness, are exacerbated by being poor. While many other medical studies have found time and time again that higher status protects our immune system.

That I do understand. To have control and agency over your own life, to be the author of your fate, is key. That is the true luxury, much more than the mere possession of money: to be able to control your fate as much as you can, and protect those closest to you from the worst of the slings and arrows. And to have something that gives meaning to your life, be that your family, friends or your faith, your work, or a book you need to write, or research you need to complete.

Pondering that, I look up Daniel Kahneman’s biography on the Nobel Prize website, and read spellbound the opening details of his autobiography there, a story every bit as gripping as his book, “Thinking Fast and Slow”:

“I was born in Tel Aviv, in what is now Israel, in 1934, while my mother was visiting her extended family there; our regular domicile was in Paris. My parents were Lithuanian Jews, who had immigrated to France in the early 1920s and had done quite well. My father was the chief of research in a large chemical factory. But although my parents loved most things French and had some French friends, their roots in France were shallow, and they never felt completely secure. Of course, whatever vestiges of security they’d had were lost when the Germans swept into France in 1940. What was probably the first graph I ever drew, in 1941, showed my family’s fortunes as a function of time – and around 1940 the curve crossed into the negative domain.

I will never know if my vocation as a psychologist was a result of my early exposure to interesting gossip, or whether my interest in gossip was an indication of a budding vocation. Like many other Jews, I suppose, I grew up in a world that consisted exclusively of people and words, and most of the words were about people. Nature barely existed, and I never learned to identify flowers or to appreciate animals. But the people my mother liked to talk about with her friends and with my father were fascinating in their complexity. Some people were better than others, but the best were far from perfect and no one was simply bad. Most of her stories were touched by irony, and they all had two sides or more.

In one experience I remember vividly, there was a rich range of shades. It must have been late 1941 or early 1942. Jews were required to wear the Star of David and to obey a 6 p.m. curfew. I had gone to play with a Christian friend and had stayed too late. I turned my brown sweater inside out to walk the few blocks home. As I was walking down an empty street, I saw a German soldier approaching. He was wearing the black uniform that I had been told to fear more than others – the one worn by specially recruited SS soldiers.

As I came closer to him, trying to walk fast, I noticed that he was looking at me intently. Then he beckoned me over, picked me up, and hugged me. I was terrified that he would notice the star inside my sweater. He was speaking to me with great emotion, in German. When he put me down, he opened his wallet, showed me a picture of a boy, and gave me some money. I went home more certain than ever that my mother was right: people were endlessly complicated and interesting.”

As a journalist, I can only agree. People only very rarely say what you expect them to say, and you can usually tell manufactured quotes in a newspaper: they never sound quite eccentric enough to be the real thing – apart, obviously, from the one thing that absolutely every neighbour says about the next door neighbour who turns out to be a serial killer: “He kept himself to himself”. I assume that few serial killers, apart from Hannibal Lecter, make particularly good dinner guests.

Over the summer, at perhaps my lowest ebb, a good friend suggested I read Viktor Frankl’s book, Man’s Search for Meaning, written after Frankl survived imprisonment in Auschwitz. By then, I knew I couldn’t continue in my old job with my health in its current state, and it felt to me as though everything I had worked for over the past twenty five years was collapsing, with nothing (as yet) to take its place.

Frankl was an Austrian neurologist and psychotherapist, as well as being a survivor of the Holocaust.

Man’s Search for Meaning, first published in 1946, is written with simplicity, directness and grace, and explains how it was that some people managed to survive the death camps even in the darkest circumstances imaginable – and not just to survive, but to find meaning, and a reason to continue to live.

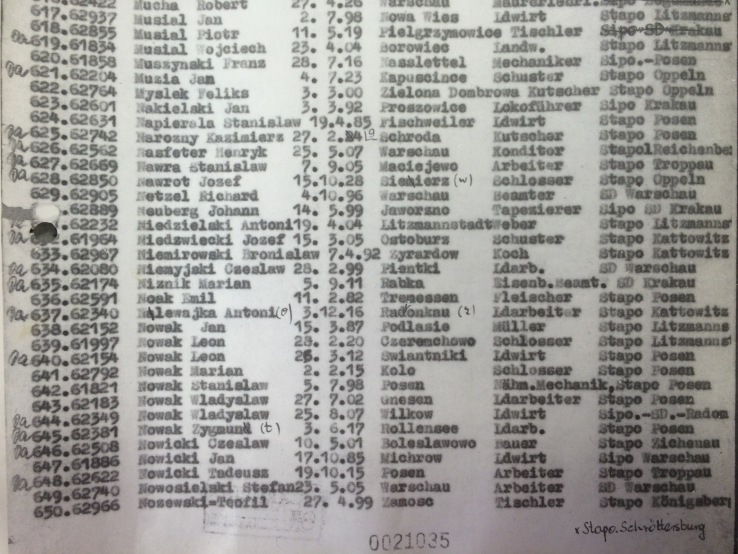

I shall never know quite how my natural maternal grandfather, Jozef Niedzwiecki, managed to survive his years as a Polish political prisoner in Auschwitz.

In January 2015, when we reported on the anniversary of the liberation of the death camp, I went to look up Jozef’s records.

The kindly archivist at Auschwitz found me three or four, and laid them out in front of me. But even as I read them, I could not find a way to comprehend how any human being had managed to live or work or sleep for even a few minutes at night in the intense cold and cruelty of a Polish winter, let alone go on to have a life that was notable for its sheer normality. At least on the surface.

Jozef’s eyes in the black and white photos are hooded, and his face betrays no signs of joy. He survived, and never spoke of Auschwitz again. I have no idea what kept him alive, or gave his life meaning through those years for – as it turned out a few summers ago – he abandoned his own young family after leaving Auschwitz.

Instead of returning home after the liberation, to be reunited with his wife and three young children in what was eastern Poland and is now Ukraine, he instead headed west, to Germany, where he met my natural grandmother in a refugee camp, had two children out of wedlock, and then emigrated with his new family to Australia, leaving post-war Europe – and his old family – behind.

Did his new wife Anna, my natural grandmother know? I am not sure. Probably not. But who knows? Many people after the war left secrets behind, and began new lives afresh. As Kahneman says, people are endlessly interesting and complicated.

Jozef became a figure of some rectitude. Known as Joe to his Australian colleagues, he was a man of few words who worked hard as a fettler on the railways.

In an age before the internet, simply disappearing, creating a new life, was rather simpler.

And it was only two or three years ago that any of this emerged, when Jozef’s daughter Maria got in touch from Ukraine with my Aunt Sonya in Australia to say that she thought they might be half-sisters. Maria is now around 80, Sonya at least a decade younger. It turns out that they are indeed half sisters.

But when they met up for the first time, what struck me most was that Jozef had given the daughters of his second marriage the middle names of Maria and Jadwiga.

The names of the daughters from his first marriage that he had abandoned.

So Jozef had not forgotten the children of his first marriage. But he had allowed them to live on only in name in his new life.

Maria and Jadwiga never saw or spoke to their father again, after they saw him being taken away by the police on some unspecified charge.

And Jozef never got in touch to find out how they were, but returned all the Red Cross tracing packages that arrived from Poland to Australia (his first wife must have had an inkling that he had survived and emigrated) to sender, marked ‘addressee unknown’.

Maria recounted the story of the last time she had seen her father, as we sat together in a small restaurant on the border of Poland and Ukraine. She looked at Sonja, held her hand, and began to cry.

“You are my sister. But you lived the life that I should have had,” she said, and wept again.

Yet we cannot live that way.

Envy eats the soul away. I have (almost) managed to train myself not to envy people with designer goods or anything quite so shallow. Neither Manolo Blahnik nor Gucci stir my desire any longer, though I admit I’d be hard pushed to turn down a Hermes Birkin bag if you offered it to me quietly as we stood together on the highest mountain overlooking the desert, with you offering it in exchange for me jumping from a pinnacle and relying on angels to break my fall.

I like to think that I’d say no, but in my current weakened state, I am not sure.

But I do envy people who take for granted their good health, who use it up with insouciant ease without even realising how precious it is to be able to lift first one leg and then another, and do that all while talking as you walk.

And I absolutely have a rich dark emerald seam of envy in my mind, somewhere quite close to the golden seam of memory and the shifting sandy layer of forgetfulness, that lights up like kryptonite in a Superman film when I sit with people with proper learning, a really proper education and expertise.

Not my shallow, journalistic butterfly mind that picks up not terribly useful facts like the tiny Berlin sparrows at my favourite café used to peck and pick the breadcrumbs up from under my feet at the book-lined café on Fasanenstrasse.

There is something about a sparrow. Why is it that they have survived so well in Berlin, but not in London? Perhaps it’s our pigeons, cockney thugs that they are. On Trafalgar Square at night, there must still perhaps be sparrows trying to sleep, as George Orwell once tried to sleep on a cold night there while being ‘down and out’ before he was moved on. In his case it was by the police. In the sparrows’ case, it will be the bigger pigeons who sidle up, fluffing up their feathers so they look even bigger than they already are, with menace in their dark eyes, and a knuckleduster hidden about their plumed person.

“Ere young sparrer,” they’ll ask. “You paid your dues to the Krow bruvvers yet, and if not, why not?” And the sparrer will cower, find a ha’penny from somewhere buried deep in its plumage, fling it at the pigeon and fly off as fast as its tiny wings can carry it.

But why is it that I write of joy and envy today, as the sun goes down over the volcano?

I think it’s because I’m the last and only one in my group today to still be in neutropenia. I could feel it as I lay on the sofa again listlessly for most of the day, idly reading and then falling asleep. I could feel it as we watched The Crown tonight (the episode called Pride and Joy, which Joy enjoyed, and so did I. Prince Philip really is terribly handsome).

And I can feel it still, even as I know it is time to go to bed to sleep properly. I shall see if Joy has popped the lavender behind my pillow again, for I need the sleep.

I am happy for the others whose immune systems have recovered more quickly. Really I am. But that worm of envy is definitely in there, too, somewhere, and I can only hope that by tomorrow, my sluggard cells will catch up.

I shall find out by midday today, Tuesday, whether I have at last emerged from my neutropenic state, and if I have, I can have the final drug infusion of Rituximab, which should wipe out the remaining B cells that have gone rogue.

And in the meantime as I lay my head upon the pillow, Maximus Decimus should feel free to pop over from the other side of the Elysian fields for a chat tonight, although I am quite sure that his first wife and children will gaze on most disapprovingly.

Fingers crossed. Be positive. Be strong.

LikeLike

Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning is a book I’d recommend everyone reads.

LikeLike

So enjoy reading these – puts so much into perspective. Will keep praying…. When you’re back come and see all the sparrows we feed daily in our garden in Battersea, and alas a sparrowhawk last week, who came for his lunch!!!

Do hope you’ve had some encouragement today.

LikeLike